I am here because of incidents a hundred years ago in Adana, a city in the far southeastern corner of Turkey.

Every family has a few cherished stories about how they came to be who they are, anecdotes of some ancestor, someone clever or determined, someone lucky, or fated or foolhardy. Certainly every Armenian family has a story about how they survived the 1915 genocide. For Armenians, these stories always apocryphal: after all, if someone hadn’t survived, the teller wouldn’t be here, and their relatives would not be here, and their children and grandchildren would not, and would never be here. Indeed, I am here because of incidents a hundred years ago in Adana, a city in the far southeastern corner of Turkey. These circumstances, including the intervention of a brave American teacher, allowed Haroutune and Haigouhi Kalpakian to survive the genocide. A few years later they emigrated to Los Angeles in 1923 with their two little daughters, Angagh and Pakradouhi, as well as Haigouhi’s younger brother. They rode the train from New York to Los Angeles where they were met by Haigouhi’s older brother and sister who had emigrated years before, and sponsored them.

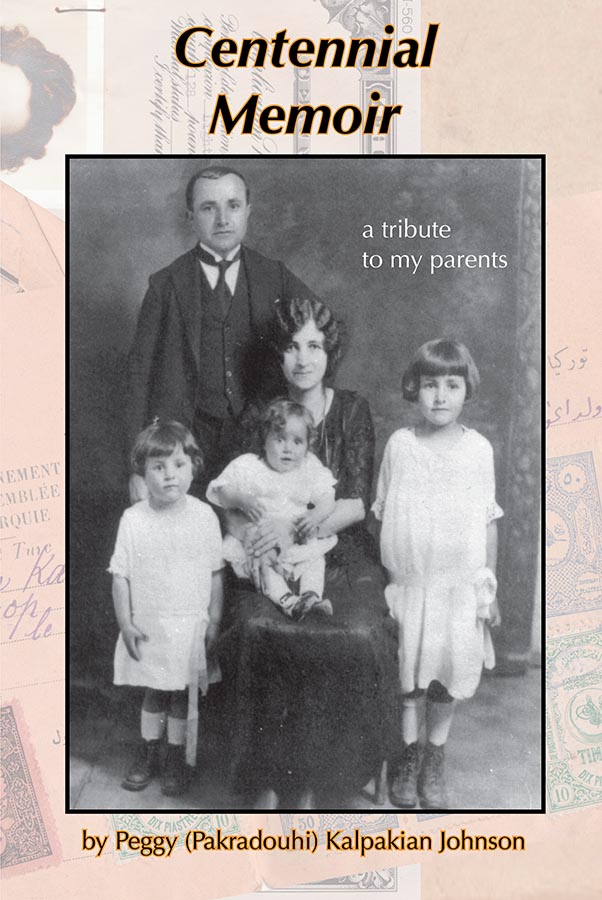

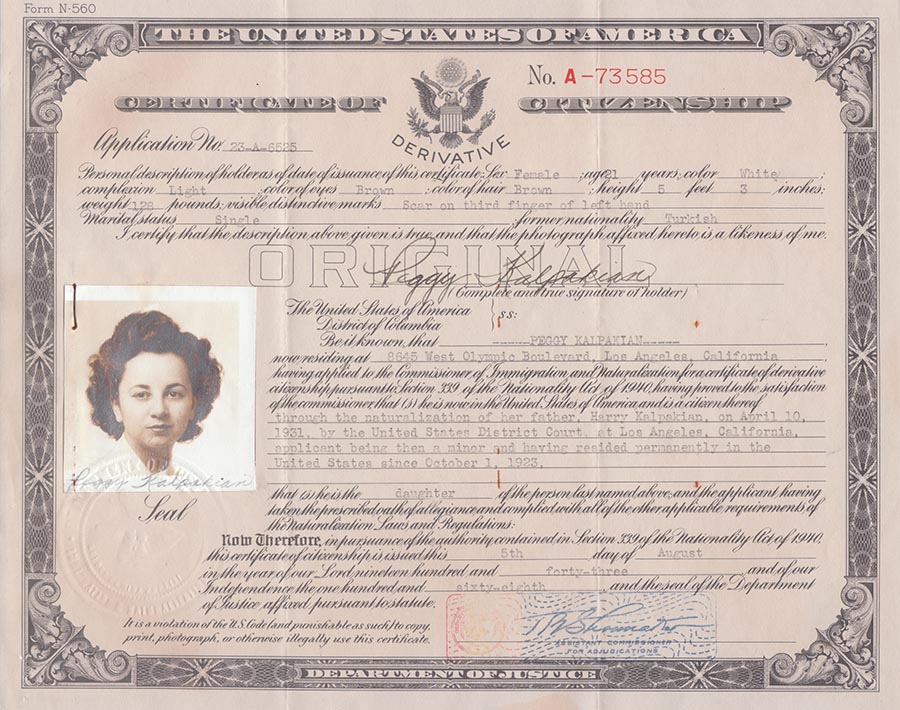

Pakradouhi Kalpakian was a toddler in October 1923. Now, nearly one hundred years later, Peggy Kalpakian (her name change is official on her citizenship papers) has written A CENTENNIAL MEMOIR. Of all Peggy’s immediate family (parents, three sisters, aunts, uncles, cousins) she is the only one still alive. The solemn burden, the responsibility of having outlived everyone impelled her to pick up the pen in 2017 when she was 95 years old. She set out to commit these stories to the page in honor of those who were gone, and to preserve their stories and photos for those who are yet to come.

Her slender, 118 page book honors her parents, their journey, their struggles in America, their becoming proud American citizens in 1931. It begins with “The Old Country,” briefly describing their lives as Armenians living in Turkey, and their marriage in October 1917. Chapter 2 recounts “The Journey,” and chapter 3, “The New Country” about their lives in Los Angeles. Peggy had thought her book would stop around 1941 when Harry and Helen Kalpakian bought the house at 8645 West Olympic Boulevard. (They would live the rest of their lives there, my grandfather dying in 1963.) But, as often happens for a writer, new ideas came to her. New stories grew out of the old ones. She had new ambitions to broaden the book beyond her own immediate family to include the lives of her aunts and uncles. The memoir bloomed into some nine chapters, plus a glossary of Armenian terms, sections on Armenian names, on family recipes, farewells, Hojah stories (folk tales that my grandfather loved to tell). The book also grew larger in scope and concept because while she was writing, we were able to reconnect with Kalpakians living in Europe.

All of the Kalpakians left Turkey after World War I, all of them into the diaspora, the US, Jerusalem, Lebanon, and Romania. My grandfather never saw any of them again. His youngest brother, Nishan traveling on a French passport, went to Romania. There Nishan married and had two children, and made a life. In 1938, on the eve of World War II, because he was not a Romanian citizen, Nishan and his family, were ordered to leave. They moved to France where they struggled during the Nazi Occupation when Nishan was conscripted. He died in 1970 in Marseilles.

Thanks to the internet (and the genealogical enthusiasms of Jenk Stephenson, husband of my cousin Patty) we reconnected with Nishan’s daughter, 85 year old Arminé Kaloustian—my mother’s only remaining first cousin. Arminé lives near Lyon, France, and one of her daughters, Astrid, has excellent English so we could email back and forth, exchanging stories and pictures. Summer 2018 we actually reunited when Astrid, her husband and daughter visited Southern California. Nearly one hundred years after the brothers Haroutune and Nishan had been torn apart, their descendants met. Though my mom could not be with us—she is too old to travel—this story too went into her book.

CENTENNIAL MEMOIR is personal, heartfelt and heart-warming. Peggy tells the family’s apocryphal tales of harrowing escapes, unthinkably fortunate coincidences in the old country. But she also tells of a charmed childhood in 1920’s Los Angeles, school days during the Depression, her parents’ careful frugality and emphasis on education. The Kalpakians assimilated swiftly, eagerly, shed their old country selves without hesitation, or a backward glance. These two photos of my grandmother document that eagerness to be American. The one, 1924, the year after they came, the other 1926, a mere two years later. Short hair, short skirt, silk stockings, high heels. I would never describe my grandmother as a flapper, but she is certainly stylish. They became American citizens, Harry and Helen Kalpakian in 1931.

Haroutune Kalpakian spoke Turkish, Armenian, a little Arabic and some French, but no English when he arrived in Los Angeles. In just a few years he went from working in a kewpie doll factory to owning a series of small grocery stores; his wife worked by his side; the daughters stocked the shelves and looked after one another. Thus, it was altogether fitting that Peggy launched CENTENNIAL MEMOIR with a party at a small middle-eastern grocery and café, Mediterranean Specialties, a favorite place of ours because the scents remind us of my grandfather’s stores.

Entering Mediterranean Specialties that afternoon, my mom shed tears of happiness.“I never thought I would live to see this day!” she cried, arms open wide, face alight with joy. She signed books, drank wine, nibbled on middle-eastern delights, and accepted the applause and recognition her hard work deserved.

That day was one of the happiest of Peggy Kalpakian Johnson’s whole life, all 97 years.

Peggy Kalpakian Johnson is at work on a new memoir about the postwar years. Stay tuned.